There has been buzz for years now regarding sexism in gaming. The discussion is juvenile in the best of days; sexualization is conflated with misogyny and denizens of nerd culture that have been historically more progressive than the mainstream, are now being pointed at as horrible sexists by usurpers that invade their spaces and bring their problems with them.

The discussion can be interesting, however. Looking at games and seeing the messages they (usually unintentionally) communicate is intriguing from an analytical standpoint. It's when the (entirely unproven) argument that there are real life consequences is insinuated that the discussion falls apart and contributes to a toxic environment, in which discourse is discouraged.

The Witcher franchise, in the games industry at least, has been a favorite punching bag when it comes to accusations of sexism. The Witcher tends to draw from actual medieval times more than most fantasy settings; it's not just the kings and the castles and the dragon mythology; it's also the politics, the values and the gender and race dynamics that play a massive role in defining that universe. The DNA of The Witcher is a double helix of monsters and the historical and cultural framework in which Slavs had had to exist in for centuries. Inescapably this leads to some fairly conservative themes. They aren't themes that are promoted, mind you; they are just themes that exist and may clash with our modern progressive sensibilities, especially when other RPGs like the Dragon Age series or just good old Dungeons & Dragons don’t shy away from progressivism.

(The following article contains spoilers for The Witcher series)

The original Witcher title took a lot of flak, after release, for being a sexist game. Part of the reason was that the story is a sausage-fest that’s very liberal with the subject matter of sexualization of female characters and approaches gender roles in a somewhat traditional fashion, especially for male characters (be warriors, be brave, protect the womenz). The primary source of contention, though, was the series of side-quests in which the protagonist, Geralt, romances female NPCs (Non-Playable Characters) and after their sexual encounter, the player is presented with a NSFW card of the lady involved. It is understandable why a mechanic which turns romance into a card collecting mini-game rubbed some people the wrong way. It seems like the definition of objectification; women in the game aren't important people with the same agency as the male NPCs; they're merely things to be collected by the player.

I've always found this view fairly myopic. The mechanic may be bad form, but it’s ultimately innocuous; it’s not pervasive and it’s versatile within the game. For one thing, the interactions are fair and straight (and entirely optional); with most of the NPCs there is no deceit and consent is entirely informed. The prostitutes of the Temple Quarter and the courtesans of the Trade Quarter ask for money to provide a service; the game doesn't feature explicit sex scenes, so the cards are the only reward (in this case, service) the player receives. The other NPCs operate on roughly the same principle; they ask for a gift or a favor and then the game provides the card. It may not sound like the healthiest worldview of sexual relations, but the female characters are always in control; they're the ones to request and initiate the encounter. It's fanservice for the (probably) male player, but the women in the game are not used or abused by the player; during the interactions, it's Geralt that has to put in the effort and prove his value to them.

Besides that, some of the cards are rewarded for forming a relationship with either Triss or Shani, the two main romantic interests with significance to the story. The mechanic is technically the same, but its value changes in those cases as they function like the sex scenes in a Mass Effect or a Dragon Agegame instead. Both of the aforementioned ladies provide two cards each; the player can receive the first card of both, but once Geralt pledges his heart to one, the player can't obtain the second card of the woman the hero rejected. Furthermore, it’s not a coincidence that while certainly sexy, the first cards both of these ladies award are not explicit; the “goods” are covered, so to speak. It’s the second card for both of them that shows their full naked forms; still a reward that falls under the category of “fanservice”, but one with significance, as the player can’t receive both of the “superior” cards, based on their choices. Whoever Geralt chooses, they're real, fleshed out characters in the game and form an emotional connection with the player, who is required to make a choice that matters.

|

| Shani's first "sex card" |

|

| Triss' second, "earned" sex card |

An interesting encounter is the one with Celina in Chapter 4. Soon after he reaches the fishing village of Murky Waters, Geralt encounters Celina who quickly jumps Geralt as long as he has a ring, any ring, to offer. Celina is a petty character who only sleeps with Geralt, because she's jealous of her sister, who is soon to be wed. She goes on to kill her sister directly after the sexual encounter with the hero, before she herself is murdered; both of them turn to wraiths and are part of a side-quest the player has to resolve. Geralt and by extension the player aren't technically in the wrong; they are offered sex and have no way of knowing what will transpire afterwards. Furthermore, these events will come to pass; even if Geralt turns Celina down, she will still murder her sister. The outcome won't change. Still, it generates a certain feeling of guilt for not seeing the massive red flags that woman raises the moment she meets the player. Celina’s presence in the story makes her a fleshed out (if unlikable) character and her card comes at an emotional or at least an ethical price. This elevates her romance above the majority of other sex encounters in the game; just like Princess Ada’s romance leads to a clue about the plot. So, the mechanic isn’t always used for titillation, but it’s versatile and adapts to the characters involved.

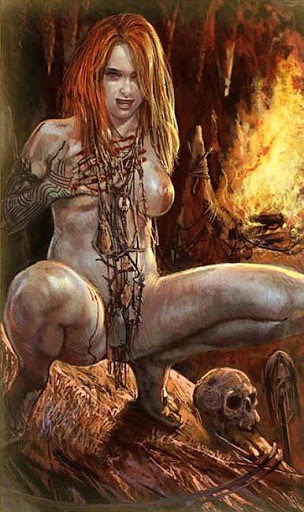

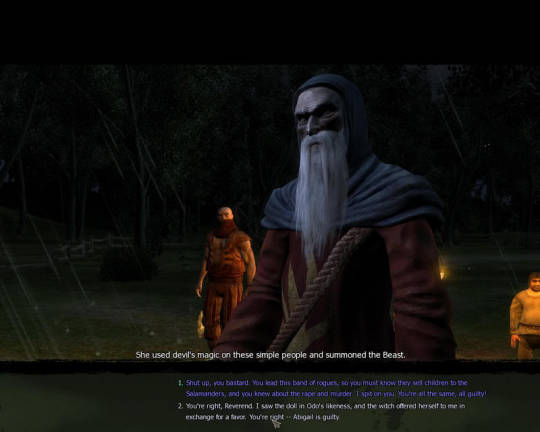

Another similar situation that points to the mechanic’s versatility is an early sexual encounter with the witch Abigail. Toward the end of the first chapter, the resident witch of the small village in the outskirts of Vizima is blamed by the local men for a number of crimes, including the appearance of the spectre referred to as “The Beast”. The village is the definition of degeneracy and the population, both men and women, are just horrible people. The story focuses more on the men’s crimes, which makes the dynamic interesting, because Abigail offers to bed the Witcher. Afterwards, Geralt and the player can choose whether or not Abigail should be held responsible, as her offer for sex can be framed as a means to manipulate Geralt and dodge punishment for her crimes. Of course, the crimes that Geralt uncovers during his time in the outskirts clearly point to the locals being the problem, so the ethical dilemma is largely manufactured, but there is an effort to have the player question if their romantic conquest of the witch and the pretty sex card, in which she’s entirely naked, contribute to the decision to either protect her or sacrifice her to the mob. That it is mostly men against one woman plays a part in this too, as sex with Geralt is one weapon the villagers don’t have available to use and at the same time their religious fanaticism quite clearly condemns her exactly because she is a woman. The execution is lacking, but the intent is clear.

|

| Abigail's allure to convincing Geralt to protect her |

|

| The head priest of the village making his case for the "evils" of being a woman. |

The system isn't fool-proof, of course; the encounter with the Morenn, thedryad from Brokilon in the second and third chapters of the game is a little bit disturbing. Brokilon dryads don't copulate for pleasure; they only have sex for reproduction. Geralt, like all witchers, is sterile; Morenn knows this and mentions it. To CD Projekt RED's credit, any effort to bullshit her on the sterility issue ends in failure; the dryad rejects the player definitively. Eventually, Morenn asks Geralt to bring her ten wolf pelts to prove he's a worthy mate despite his infertility. The encounter isn't technically all that different from any other; it's just uncomfortable, because the dryad has to circumvent her people’s entire culture for one fuck with some random witcher. It’s a sacrifice that Geralt isn’t asked to make himself, which makes the playing field uneven and puts Geralt in a dominant position with control over Morenn.

Blaming this mechanic for sexism is also silly for a reason a lot more fundamental to the medium; the NPCs aren't women, they're objects inside a videogame. This is a hard position to understand, particularly for those looking from outside in, people who are not aware of how videogames work and judge them using the same tools as they do other media (oh hai Anita). Everything in a game is an object. No matter how immersed or absorbed they are in a game, players know they only play a game each and every single time; where outsiders look at NPCs and see "gender", gamers see rules, objectives and tools. There is a reason nobody ever threw a fit (unironically, at least) about the countless men that are getting mowed down, typically, in games; they aren't men, they are obstacles to an objective, to winning the game and they have to be removed. For the outsider this sounds terrible, because they look at those obstacles and interpret them based on their appearance (i.e. human). They are not; the player knows they don't have feelings, they don't have independent thought, they don't have families. Everything that makes real people matter is entirely absent from videogame NPCs.

The principle is the same in a mechanic like the lady cards in The Witcher.Where many see "women", gamers see "means to an end". Their paths are predetermined, they have no life before or after their encounter with Geralt; they only exist in that moment that the quest needs to be completed. That they look like women is a matter of logical consistency (Geralt is a straight man) and aesthetic. There is no deeper meaning to that and no influence in real life. The ones that are more than just that, namely Triss and Shani, are important characters in the story that the player connects to emotionally and, as explained earlier, offer their sex cards less as a reward and more as the fulfillment of the romance. There is the argument that the way these objects look is enough to influence the behavior of the player, but not only is this unproven in regards to video games in particular, the tools needed to legitimately influence gamers’ ideas during gameplay are far more complicated than a 3D model and a pretty texture. If mechanics don’t contribute to the message, the influence of story and aesthetics is minimal, if not non-existent.

Assassins of Kings, the second Witcher game, doesw away with the mechanic; romancing in the game is actually a lot less important than it is in the first game. Even so, the romance between Geralt and Triss or Geralt and Ves was heavily publicized, presumably because The Witcher 2 featured really pretty characters for its time and, well, everyone likes sex.

The first accusation of sexism I paid any attention to came from Liana Krezner, an independent games journalist and self-proclaimed feminist. You'll see Liana popping up quite a bit in my pieces, because despite political disagreements, she has a good head on her shoulders; she knows sociological theories, she knows how to apply them (better than I can), she treats everyone like a person and she knows videogames, unlike certain other feminists that dipped their toes into this growing industry’s cash pool.

So, Liana is uncomfortable with Triss in The Witcher 2, because the character's introduction in the game is when she's butt-naked next to a boxers-wearing Geralt (pointing to double standard for titillation) and because "you can literally forget about her", as Liana puts it, later when she is kidnapped. It took me a while to see her point; particularly, it took me three replays and a full view of the game from both “paths” to understand where she is coming from.

|

| Triss' introduction in "The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings" |

Assassins of Kings features several female characters who are, on their own, absolutely powerful. Triss, Sile and Phillipa are powerful sorceresses, once members of the famed Lodge (which had influence over the fates of Kingdoms). Ves is the sole female member of Temeria's Special Forces, the Blue Stripes, pointing to great skill that makes her equal to her male comrades-in-arms, despite physical and social obstacles she’d have to overcome to be in that position. Saskia, the leader of the revolt in the town of Vergen is literally a dragon-in-disguise. There are smaller characters of lesser importance to the story, but let's focus on the above.

Where I did observe sexism in The Witcher 2 in my last playthrough wasn’t in the characterization, but rather the utilization and fates of the aforementioned characters. Their involvement in the story is auxiliary more than contributory. Sile is weak-willed and has an agenda. She helps Geralt with the monster Kayran and she’s one of the two sorcerers in the second chapter to try and lift King Henselt’s curse. As the player learns in the end, she is being played by the Kingslayer witcher Letho of Gulet. Her fate is in the hands of the player; she can either be rescued as a pathetic failure, or left to die a gruesome death. Sile’s story in The Witcher 2 is entirely one of meaninglessness; she’s a tool and not even an effective one. Whether she survives the game or not, she’s a character to be looked down to with nothing less than utter pity.

Saskia's role in the game isn't communicated to the player, should Geralt join Roche instead of Iorveth at the end of the first chapter. Unfortunately, there is very little of her even if the player does follow Iorveth. The great “virgin peasant" girl that carries the title Dragonslayer and leads a revolt against King Henselt of Kadwen is written out of the story for the vast majority of Chapter 2. When she's not in a coma, she's being mind-controlled by Philipa Eilhart. The actual, free Saskia appears little in the game; the character redeems herself after Geralt gets her back to normal and she successfully wins the war with Henselt (and turns into a freaking dragon while doing it), but the fact remains that the game hypes her up at the beginning of Chapter 2, all progressive-like and then promptly writes her out of the story. Like many things in the Witcher games, she is forgotten about and her actions have no bearing or impact on anything.

Phillipa feels like a bad knock-off of the person she used to be in the books. The unofficial leader of the Lodge, “Phil” is not just conniving and scheming; she's effective. CDPR captured the "scheming" part in The Witcher 2, but failed on everything else. She's the one holding Saskia under her control, but her larger plot isn’t well-thought-out. Phillipa is not nearly as layered as she is in the books or in The Witcher 3. Her fate in the second game is gruesome; King Radovid of Redania captures her and pokes her eyes out. Then, she quickly exits the game. Her plan to control Saskia fails, should Geralt join Iorveth and all her efforts go to waste not simply because the hero ruins her plans, but because she is tortured and then turns fugitive, with her actions not impacting the third chapter of the game in any way that truly matters. She’s more useful in the game as a quest-giver, who doubles as an exposition-puking device than a character with agency and with clear contribution to the story. Little would be have been lost, had she been replaced with an original character (like her “pet-lesbo”, Cynthia).

(Pictured Below: Phillipa Eilhart after King Radovid tortures her in The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings)

|

| Phillipa Eilhart, following torture by King Radovid in "The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings" |

Ves doesn't have a large role in the game, she's mostly significant for being a romance option, if Geralt follows Roche in Flotsam. There are little annoyances during dialogue scenes that seem to focus on Ves being the only woman amidst a military unit staffed exclusively by men and Roche is a tad too overprotective of her for comfort (it feels less like caring for Ves andmore like caring for the “woman”), but they can be waved away as part of the outdated societal standards of the era in human history the game thematically reflects. The issue with Ves is that her only contribution to the story is being raped by King Henselt. She's not held down, she's coerced; she stops resisting Henselt, when he blackmails her that he will kill every single one of her comrades should she continue to fight him. It's a move that requires massive strength of character, but it's also one that's executed badly; Henselt kills everyone anyway and the way the story is told, Ves' rape seems to be just the icing on the cake of vengeance for the player to finally gut King Henselt and put an end to his reign. Ves is written to be a badass, the female commando that’s equal, if not better, than the men in her unit and yet, the way the game handles her rape, it manages to remove all her agency as a character.

|

| King Henselt coercing Ves to have sex with him |

Finally, there is Triss. Triss really suffers in the first two games; in the first one, she is a stand-in for Yennefer, acting entirely out of character for the books' Triss Merrigold. In Assassins of Kings her characterization is on-point, but she barely matters in the story at all. She is introduced entirely naked and diddled by Geralt (and, by extension, the player). She shows up again at the end of the prologue and she hangs around during Chapter 1, but her investigation gets her kidnapped. Geralt wants to rescue her, but for the entirety of Chapter 2, he has no leads, so he spends days doing everyone else's bidding instead of focusing on finding her trail; a choice not just contrived and insensitive, but also nonsensical, as Geralt’s real goal is finding Letho and he is the one who captured Triss in the first place. Then, in Chapter 3, the option to save her comes up, but Geralt can choose to ignore it and actively choose a different path in the quest. Should this happen, Letho frees her on his own and she joins Geralt after the last battle to finish the game. Reminder here that for all intends and purposes, she's literally Geralt's girlfriend during this game.

This is where Liana's point becomes valid; she's an important character from the books and a capable one at that. She's someone who not only Geralt has always had feelings for (even if he was primarily obsessed with Yennefer), but she's absolutely his girlfriend in The Witcher 2 as well. What does she get for all that? Being eye-candy in a couple of scenes and then disappearing and being forgotten about by the one person that's supposed to care about her. If “love” is what Geralt shows Triss in this game, I heartily hope my romantic partners will hate me enough to fantasize about stabbing me in my sleep instead.

Part of me thinks that they wrote her out, because she is too powerful; had she remained in the game during Chapter 2, she'd have replaced Sile and Deathmold (both of who had their own agendas vital for Roche's path) and she would've seen through Phillipa's lies about Saskia in Iorveth's path. Whatever the reason, the fact remains she is treated badly both by the supposed heroes of the story and by the story itself.

|

| Render of Triss Merrigold from the second game, which made it in a collection for the Polish edition of Playboy Magazine. |

The issue, ultimately, isn't the treatment of any single one of the aforementioned characters, but the pattern that has formed. Each one of the central female characters in the story is kidnapped, beaten, tortured and may end up raped or dead. This becomes even worse if we account for Sabrina Glevissig; Sabrina technically isn't in the game (she’s another Lodge member from the books), but she's the powerful sorceress, who cast the curse on King Henselt and who was burned alive at the stake for her actions during Kadwen’s battle against Aedirn a few years before the game takes place.

The source of the problem is two-fold; one is simply the fact the story of The Witcher 2 is garbage. It sounds like a cop-out excuse, but that game serves as the bridge between the books and the third game. It exists to make references and reset the tone of the series from the radically different first game. The plot is unfocused and regardless of how well characters fare in it, regardless of their gender, every chapter of the game (including the prologue) feels like an entirely different story on its own with thin connective tissue to string it all together. A lot of the characters come in simply to provide quests for the player to complete rather than be active parts of a larger story. Even Geralt himself, the hero of the story, spends most of his time doing errands. His ultimate goal is to clear his name and prove he didn't kill King Foltest, but Letho himself disappears when it's convenient and outright decides to let himself be found when the time comes for the game to conclude. Ultimately, Geralt and the player win on a technicality. Their actions don’t get them closer to their goal, they’re simply killing time for at least 25 hours of gameplay, until the story resolves itself. If the main hero and the main villain can't be tied into organic storytelling, it's hard for any of the secondary characters to be.

The other facet of the sexism found in The Witcher 2 is the clumsy attempt to replicate the atmosphere of the books. This is prevalent in both the first and the second games. The Witcher universe is darker and more cynical than most fantasy settings; everyone’s a bastard, the heroes have way too many passions and flaws and every victory is Pyhrric. CDPR was trying a little too hard in the first two games to get that point across, so they decided to tackle their stories and settings the same way a bull tackles a puppy wearing a red collar.

While fetching a red ball.

On the surface of Mars.

While fetching a red ball.

On the surface of Mars.

In a weird way, their sexism is both intentional and unintentional. They make clear attempts to demean women in the second game; not because they think less of them, but because they think that men in the world of the Witcher (particularly bad men) think less of them. That's why Sile gets played, why Ves is raped, why Sabrina is burned and why Phillipa is tortured; not because they're not powerful, but because the men around them are evil and direct all their hatred at them. A similar example from the first game would be that incident with Abigail in the outskirts of Vizima, which in itself is a reference to a similar situation from the original literature. What all of it really is is an extension of the violence that permeates the games and is usually directed at and perpetrated by male characters. Only Geralt, Roche, Dandelion and Zoltan are the good male characters; maybe Letho after he reveals his plan at the end (depends on your point of view) and the dwarves of Vergen, but they are bit characters. Henselt, Deathmold, arguably Iorveth and Captain Loredo are villains; not just villains, but rotten to the core, truly vile people. CDPR probably thought they were being balanced while keeping in tone with the world they had set up.

The decision to frame the world like this was, to say the least, unwise. Not only does it become patently ridiculous, because it alludes to mustache-twirling villainy without the Saturday Morning Cartoon censorship on violence, but also because there are unintentional double standards that form. Geralt's clearly the focus of the game and Roche maintains his position as the leader of the Blue Stripes. The worst thing that happens to him is that Henselt executes his entire unit, for which he gets to have his revenge. Dandelion and Zoltan are secondary characters without their own story arc to begin with, Iorveth disappears after the first chapter and Letho can walk away free, should the player choose it. The only ones that find a deservedly bad ending are Henselt, Loredo and Deathmold and even that's only if Geralt follows Roche for Chapter 2. The male characters, particularly the heroes, make no sacrifices and don’t really lose their status or their position, let alone their lives or physical well-being. The female characters, both good and bad, do. So, in the end, it seems like if you're a man in The Witcher 2, you may be a piece of shit, but at least you're safe (or at least deserving of your fate and central to the story), but if you're a woman, you can be powerful, but you are still nothing more than someone else’s victim.

|

| Roche castrates Deathmold and kills him. |

I'm convinced that's not the message CDPR ever intended to communicate. Whether they were trying to adopt the cynicism of Sapkowski’s original work a little too hard or they were drawing from the bloody and oppressive history of their own Slavic people, they just stumbled a little along the way. It should be noted that any observed or perceived sexism in the title is limited to the narrative. Unlike the first game, where the accusations came from a mechanic, the second title in the series keeps narrative and gameplay separate to an almost worrying degree. This is what makes The Witcher 2 a game easy to lose interest in, especially if you’ve played it before; it’s also what overstates the problems with the gender politics in it, as player agency is removed and detached from the story. Where the first game’s sex cards relied on player input and could be interpreted through player choice and mechanics, gender dynamics in the second game force the player into a passive position as an audience with no involvement in the message the narrative puts across.

In all fairness, CDPR never really managed to find the fine line that the original author walked; the third game gets as close as any of the Witcher games, but comparatively it’s a little too soft. The majority of even the villains in the game have enough nuance for their motivations to be at least understandable, if their characters not outright sympathetic (e.g. The Bloody Baron). There is a distinct lack of the rotten, no-morals society present in the books and in the first two games, outside of maybe some monsters (like the Crones) and the low-level mob bosses (particularly Whoreson Jr). The shadow of war that forces the hands of many characters in the game gives the world a perspective that’s distinctly missing from the rest of the Witcher mythos.

The Witcher 3 did, however, manage to do a much better job with its female characters. The new characters, like Yennefer, are layered and interesting with their own agency and even returning characters fare better; Phillipa exacts her revenge on Radovid, recovers and moves on to try and rebuild the Lodge. Ves does something stupid, but she’s treated as a soldier and not simply as the “woman”, despite Roche not hiding his personal fatherly interest in her. Triss is a better character than either the other games or even the books, staying loyal to her caring demeanor, but moving out of the shadow of the protagonists to do her own heroic deed and grow as a character.

The best example of a female character in that game, however, is Ciri herself. Despite starting off as both a damsel in distress and a bit of a MacGuffin, she grows and she does so through gameplay, which is what gives her the edge over more prominent characters in the story, like her adoptive mother. As mentioned, the strength of a game is in its gameplay and no video game story is complete without player input. Ciri’s use in The Witcher 3 fleshes her out in a manner simple and direct, but effective nonetheless; when players first get control of her, she’s lost in the woods, accompanying a young girl (mirroring her state, at the time) and she needs to brew some Cursed Oil to deal with one measly werewolf. It is significant that she mentions how Geralt would be better than she at hunting the werewolf. The last time gamers play as Ciri in the campaign, when the character has gained full control of her powers, she one-hit-kills warriors of the Wild Hunt and makes short work of Caranthir, one of the Hunt’s highest-tier generals. She’s so powerful, in fact, the game has to switch back to Geralt just to present some form of challenge to the player (which is in contrast to her comments earlier during her werewolf hunt). This simple method does wonders to show how powerful Ciri is and develop her character throughout the story, even though she gets less screen time than other female characters.

|

| Ciri versus the Wild Hunt General Caranthir in "The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt" |

Sapkowski knew how to give his female characters agency in the story, but without shying away from really disturbing imagery. One of the scenes seared into my brain with disgust is one in which a bounty hunter is parading a teenage Ciri in an arena and forces her to fight and a rich socialite pleasures herself in the audience, at the sight of her acrobatics and the blood and limb splatters. CDPR never managed to find the trick to this; but their efforts are commendable, regardless of whether they tripped on their own shoelaces at the attempt in the first two games or they toned things down a tad too much in the third game. Perhaps the difference between writer and developer is simply a matter of skill or simply a matter of age; they both share the same cultural and historical background, but the author would’ve lived closer to times less fortunate for the Polish people than the considerably younger game devs.

Ultimately, the source of any sexism in The Witcher 2 doesn’t derive from ill-intend or some fiend-in-the-closet social structure intended to downplay women; the issue is structural and the source is the way the story itself is set up. One can argue what it is that led to this structure to begin with and there is certainly some truth in the idea that, before The Wild Hunt, the Witcher games were certainly made with a primarily male audience in mind; but it’s far more interesting to see how those games missed their mark in their effort to communicate their themes in regards to the source material and how that material and the local culture might have affected the work as a whole. If social conservatism and outdated ideas about gender roles affected the quality of the story, it was in the context of authenticity to the source material and as a sad tribute to the historic hardships Slavs have faced.

Furthermore, looking at the evolution of the Witcher series in terms of tackling social issues within a historic context that was a lot harsher and placed far less value on progressive ideas, it’s worth pondering whether or not it’s even possible to make a game that would be thematically loyal to such a context and still be acceptable by our modern societal sensibilities. Is the fact that gamers are primarily men a factor that could contribute to this, for example? Would women gamers have a problem with it? What’s the right way to go about it? Normally a well-defined framework should be adequate to portray such a world, but considering the importance of player input, the question becomes a lot more complicated. Women gamers haven’t really had a problem playing male power fantasies, because player agency downplays the gender of the protagonist and focuses on skills and abilities through a system of success and failure, in which players of all creeds are directly engaged. But in the case of a narrative and a world that is specifically designed to be patriarchal, does player agency hold the same effect?

The usual suspects that exist to nitpick and rage about everything have raised their voices even against medieval-themed fantasy games that go out of their way to be progressive, authenticity be damned (particularly Bioware RPGs). Do their voices matter in the development of video games and how much can they affect not only the development, but also the reception of a game? Should their voices matter even that much, if the framework supports a game’s thematic direction?

These are all interesting questions to ponder when talking about social issues in gaming, without ignoring the context in which these games are made. Movies and literature have both suffered from social progressivism in the sense that it has become not only the norm, but largely a requirement for a piece of fiction to be acceptable. There is a fine line between overt bigotry and a historically or thematically accurate framework and so-called “passive” media have had trouble differentiating between the two. Gaming has the chance to dodge that problem, because of its reach and, primarily, because of the importance of game mechanics and player agency. It’s not a coincidence that the sexism that is observed in the second Witcher game is isolated in the narrative and it’s entirely detached from the game mechanics.

Sadly, I doubt either game development or game analysis will go down that route, when manufactured outrage provides both money and a feel-good-emotion of false moral accomplishment. Still, if this discussion does happen, the evolution of the Witcher series, which went from “collectible lewds” to “playing as the most powerful person in existence”, is certainly a good place to start from.

No comments:

Post a Comment